Ancient Echoes, Modern Reverberations: An Interview with Professor Claire Catenaccio on the Continuing Resonance of the Classics

In this interview, Georgetown Humanities Student Fellow Julian Zeitlinger interviews Professor Claire Catenaccio from the Department of Classics about Classical Reception Studies, a sub-field of Classics which examines modern works of art and other cultural phenomena influenced by Greek and Roman antiquity. Professor Catenaccio also discusses how Classical Reception Studies has evolved over time and how the Classics and the internet intersect today.

Claire Catenaccio is a scholar of Ancient Greek literature, particularly drama, and its modern reception. As a dramaturg and director, she has worked extensively with contemporary stagings of ancient texts. She is the author of Monody in Euripides: Character and the Liberation of Form in Late Greek Tragedy (Cambridge University Press, 2023), which explores the rise of solo actor’s song in Athenian drama. Catenaccio is Assistant Professor in the Department of Classics, College of Arts & Sciences, Georgetown University.

Julian Zeitlinger (C’26) is a junior in the College of Arts & Sciences, Georgetown University, studying Government and Classics. He was a 2023-2024 Georgetown Humanities Student Fellow. In this role, he supported the work of the Georgetown Humanities Initiative to enhance and support humanistic research and teaching across the University. Zeitlinger initiated this interview in order to explore his interest in Classical Reception Studies with a faculty expert.

Q: To someone who may be unaware, how would you describe the field of Classical Reception?

A: Classical Reception is the study of everything inspired by the Classics. This includes a huge swath of literature, drama, music, philosophy, and other art over the last 2000 years, as well as politics and history.

Q: How have the field, and attitudes towards it, changed over time?

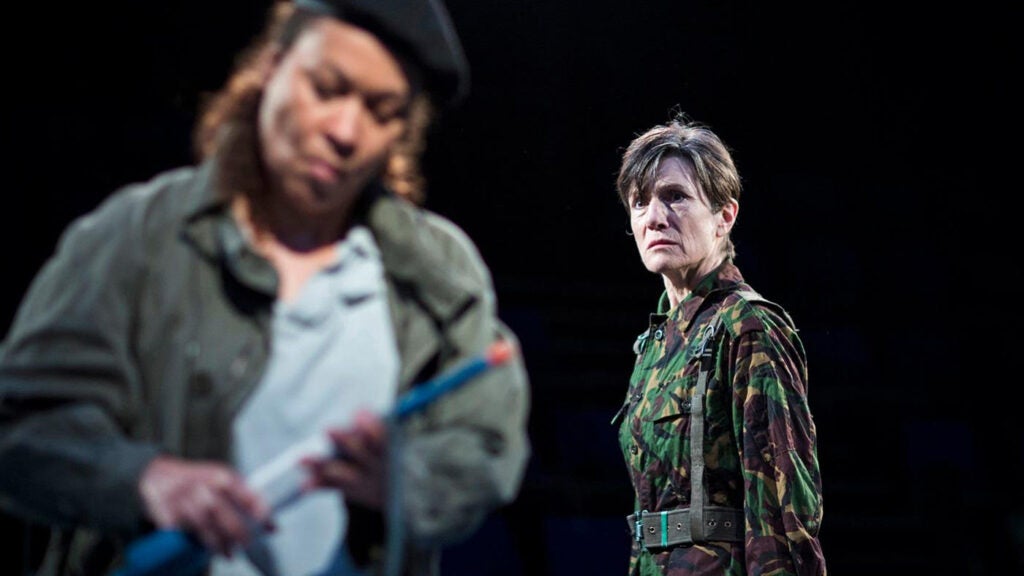

Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in a performance by Phyllia Lloyd (2019), with an all-female cast and set in a women’s prison. Photo by Helen Maybanks. Donmar Warehouse, London.

A: Classical Reception as a field is relatively new, although people have been doing this work for hundreds of years. When William Shakespeare set out to write his play Julius Caesar in 1599, I don’t think he thought of it as a work of reception, although nowadays that’s one way we might categorize it. As a scholar of Classical Reception studying this play, you could analyze how and why Shakespeare’s version differs from the account of Julius Caesar’s life that he read in Plutarch’s Parallel Lives, for instance. What is Shakespeare saying about rulers, about men in power? In earlier periods, some Classics scholars might have seen Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar as a devolution from the original, a falling-off. This assumes that there is an original, “true” account of the life of Julius Caesar, and that Shakespeare produced one that is inaccurate, diluted, or aslant. And that’s not even taking into account the fact that Plutarch wrote 150 years after Caesar’s death, and that Shakespeare read Plutarch’s work not in the original Greek but in the English translation of Thomas North! But today, and over the last thirty years, scholars have started to see works of reception as important and authoritative in their own right. Instead of thinking about an original and an inferior copy, many scholars now choose to see ideas about antiquity as always in circulation, always being discussed, always being renegotiated. They’re cultural currency. Any articulation of those ideas that has validity as a work of art can teach us something.

Q: How do different artists address the tension between being faithful to the original and rethinking it for a contemporary society? Is this even the right way to think about it?

A: It’s different in the case of every artist. It’s a truism that all art is about other art. As Mick Jagger said, “There’s nothing new in rock-and-roll.” This is especially true for artists today, who are steeped in influences across many thousands of years. There’s so much information available now, so many images, more than at any time in history. A contemporary artist who is reacting to a Classical source will often find something in the ancient work that hooks them. For instance, various modern works inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses have investigated the question of how a woman feels in the aftermath of abandonment, or the question of how a young man deals with his powerful father, or the question of how to represent a great ruler’s life. The artist may stay true to an abstract notion or question, rather than trying to recreate the entire original piece of ancient art.

Q: As a scholar, how does studying contemporary receptions, such as Hadestown, differ from older receptions, such as Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar?

Hades (Patrick Page) and Persephone (Amber Gray) in Hadestown, National Theatre, London. Photo by Helen Maybanks. Copyright National Theatre, 2018.

A: Personally, I love to look at works that are still relevant in some way. Shakespeare is a great example, because you don’t just have double vision with Shakespeare, you have triple vision. As a scholar, you can consider the ancient sources, you can consider Shakespeare writing in London around 1600, and you can consider reperformances of these plays today in theaters across the world. If you just look at antiquity and then at Shakespeare, you’re missing a part of why these works continue to resonate with audiences in 2024. That said, it is great writing about very recent works of reception because there are so many different kinds of evidence to evaluate. If you’re writing about Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, you’re mainly dealing with Shakespeare’s script, and maybe you can look for little snippets of evidence here and there about people who saw the play in 1599. But if you’re writing about something contemporary, like the Broadway musical Hadestown that you mentioned, you can go see it live, read reviews, look up photographs, interview the creative team, stream the soundtrack, and watch videos of the performance. This requires flexibility in dealing with all different kinds of evidence. I find that to be a lot of fun.

Q: There have been studies on Classical Reception in a wide variety of media, from films to political speeches. How far does the field of Classical Reception range?

A: The possibilities really are endless. I have a student graduating this year from Georgetown who wrote her thesis in the Government Department about the use of Classics in alt right circles on the internet. She was inspired by the viral meme “What’s your Roman Empire?” Why did that meme catch on? What does that meme say about our society? What does it indicate about gender or different perspectives between men and women? What is it telling us about humor? Next year, I will work with a student in Classics who’s writing a thesis about fanfiction, especially queer fanfiction, that features the mythological characters of Hades and Persephone. In that case, the research question may revolve around how marginalized groups adopt the Classics and make them their own. Both of those projects are entirely legitimate uses of Classical Reception, and there are many more.

Q: Elaborating on that, what do you think about the intersection of the digital world, social media, memes, and Classics today?

A: Anything that gets people in the door is great, in my opinion. I love a meme. The Classics have always had a trickle-down effect in culture, and they still do. Today you might laugh at a meme about the Trojan Horse on your Instagram feed, and then later this week go see an exhibit at a museum showing artifacts from ancient Troy, or read a review of Emily Wilson’s new translation of the Iliad. I think it’s been true for centuries that if you really want to understand and appreciate art, culture, or history, you have to learn something about the Classics. Now this information is more widespread than ever before. It’s not just for the elite. Even if you want to react to a Roman Empire meme, you need to learn something about the Classics. And no matter what gets you there, the material really rewards further study.